“I know what nothing means, and keep on playing.”

This line from Joan Didion’s second novel, Play It as It Lays, brilliantly encapsulates the cold disillusionment of 1960s Hollywood. In the novel, Didion metaphorically bemoans the gratuitous, melodramatic, and otherwise empty cinema culture of the time. While there were few attempts at making anything worthwhile, Hollywood kept churning out a litany of films, each more vacuous than the last. Audiences were saddled with films like Valley of the Dolls, which one critic described as having “no more sense of its own ludicrousness than a villager stumbling in manure.”

Now, I find myself feeling the same way about Kenyan cinema. I do not intend to sound cynical, but I wonder how long we are going to “keep on playing,” even when we already know what nothing means. How long are we going to keep making films about nothing, films that say nothing, lack artistic merit, and are only as memorable as a passing TikTok trend?

Kenyan cinema as it is today is devoid of any cultural significance beyond the overplayed crime trope that hasn’t been captivating enough or cultivated a stronger identity since Nairobi Half Life in 2012.

Nairobi Half Life continues to wield the kind of impact other Kenyan films can only covet from a distance. Its innovative direction, the brilliant and provocative performance by the likes of Maina Olwenya (rest his soul) and Joseph Wairimu, the riveting narrative, the natural dialogue – yet none of these alone can explain why the film had the impact it did or why it’s still memorable 12 years later. That honour is reserved for something film critic Todd McCarthy of The Hollywood Reporter described as “fundamentally honest and vividly realistic.”

It’s the way the camera glides through familiar Nairobi streets. It’s the relatable story of a young, gifted but struggling Nairobi artist forced into unscrupulous underhand dealings to make a living because, in Nairobi, art doesn’t pay. Or when the film subtly announces its uniquely Kenyan perspective by rewriting a Quentin Tarantino homage in the opening scenes where Mwas (Joseph Wairimu) changes the plot in his retelling of the Kill Bill film so that Bill himself, rather than Bill’s and Beatrix’s trainer, teaches Beatrix (The Bride) the secret technique she uses to kill him (Bill). This is a Kenyan story, Nairobi Half Life says. This is a film with Kenyan aesthetics and Kenyan sensibilities, made for Kenyans, not the West.

Kenya’s 2010s were a period of urban population boom. The nation was healing from the wounds of the 2007 post-election violence, there was a new, more progressive constitution, the economy was holding steady, and Nairobi was bustling with hope. Skyscrapers were mushrooming all over Upper Hill and the newly constructed Thika Superhighway was East Africa’s hallmark of sophistication and class. For the first time, the country was optimistic of vision 2030. This optimism cascaded to the youthful population in the countryside who moved to the city en mass with dreams of securing better futures. Nairobi Half Life captured both the optimism and struggle of rural-to-urban migration at a time when Nairobi was seen as a haven of opportunity. These migrating youth would however grapple with disillusionment upon encountering the hardships, high crime rates, job scarcity, and the overwhelming cost of living in a city just learning to house a bustling young population.

But since Nairobi Half Life, I don’t know what the industry has been doing. Has there been anything truly innovative and provocative in the last decade? Okay, maybe just a film that has stuck with you? A dialogue you can quote in your sleep? An action sequence glued to your mind? A character you found rivetingly layered? Nothing? Guessed so. You remember nothing because our industry doesn’t make films, we make soulless tropes that aren’t supposed to be remembered beyond 90 minutes runtime or so.

Do you remember Nafsi, Uradi, Click Click Bang, Disconnect, Bangarang, Sincerely Daisy, or Mission to Rescue? I liked Supa Modo directed by Likarion Wainaina. It currently has a 90% critic score on Rotten Tomatoes with audience reviews like, “a great movie with new ideas and very captivating”. Supa Modo means a lot to those of us who grew up in the 2010s, sneaking into dark ‘theatres’ to watch DJ Afro films, and later grappling with the wrath of our mothers who vigorously employed kiboko to expunge ukora from us. But this film disappeared as quickly as it came, owing in large part to its dialogue (we’re also not very good at writing kids). I also felt that the ending felt hurried and unearned.

I loved Jennifer Gatero’s An Instant Dad, which was released in 2023 but is now so distant in my mind that it could as well have come out ten years ago. In the film, writer-director Gatero brilliantly captures that whacky Nairobi humour in a time-tested father-daughter dramedy that loudly ached for a B-plot. And despite achieving some aesthetic visuals and milking starling performances from her small cast, Gatero fails to do anything novel or culturally intrinsic with the father-daughter story. In the end, An Instant Dad plays out like Dwayne Johnson’s The Game Plan -except it lacks a B plot and Blessing Lung’aho is a much better actor than Johnson. What’s Gatero’s distinct take on this subject? I wondered when the credits rolled. Still, I must commend her for her minimalist approach to storytelling; first in Nairobby and then An Instant Dad.

The fact that our directors’ unique personalities, sensitivities, and aesthetics don’t come out clearly in their films is something I believe is largely hindering the growth of our industry. There’s no new story under the sun – only storytellers who curate a sense of singularity by incorporating their personalities and their idiosyncratic perceptions of the world into their work. So, while Shakespeare tells a tragic love story of two lovers who kill themselves because of their families’ disapproval, another person could tell a tragic love story of two lovers who first kill their families before killing themselves.

Great filmmakers are not smarter than other people. They don’t know things that other people don’t. They are not trying to provide a syllabus to life. They’re just really good at being truthful and creatively using their personal experience to bridge the gap between people. Great filmmakers are just people with experiences they want to shout about to see how many people feel the same way so we can all be less alone. Isn’t that the purpose of art anyway? An exploration of our shared humanity?

So why do all Kenyan films fade into oblivion as soon as they are released? Why do they feel so soulless? Why do they all have the same bland vibe to them? Why are they so forgettable? The answer is pretty simple: they are nothing that keeps on playing.

In Kenyan cinema, the story is always generic: an academically gifted kid from poverty who somehow makes it to the university, only to be ensnared in crime. Oh, the soccer-talented kid from the slums who gets mixed up with the local gang and soon starts shooting guns instead of balls. Perhaps these stories would have been more relevant back in the 70s and 80s when the likes of John Kiriamiti towered over the local crime scene like Colossus. But our society has since evolved, and culturally, we are not the same as 30, or 40 years ago.

Where are the films that reflect our present political and social realities, that encourage us to ponder the human condition rather than the artless over-the-top poverty-porn and crime fluff? Our storytelling lacks what Martin Scorcese describes as “revelation, mystery or genuine emotional danger,”- the hallmarks of great cinema.

What makes a film memorable and truly great? For a start, there must be a perfect balance between the film’s entertainment value and artistic value. American neurophilosopher Erik Hoel brilliantly explains this: “Entertainment, etymologically speaking means ‘to maintain, to keep someone in a certain frame of mind’. Art, however, changes us.” This ability to shift our perspective while keeping us entertained is what makes any work unforgettable. Michelangelo’s David is not a masterpiece merely because it’s beautiful to look at, it’s great because it challenges your perception of the limitations or lack thereof of mankind, and long after you’ve seen it, you never forget it.

Sophia Coppola, the daughter of director Francis Ford Coppola, is a perfect example of a filmmaker who has been able to seamlessly balance artistry with entertainment. Her films, always less driven by the plot, share common themes: the emptiness of living in excess, alienation, and girlhood. On screen, these themes are interrogated through picturesque, delicate visuals and saturated frames as in Marie Antoinette (2006), or a more muted palette as in The Beguiled (2017). Coppola also employs a lot of visual metaphors, using vapid imagery to communicate moments of ennui and loneliness or slow zoom-ins to evoke feelings of confinement, as in Lost in Translation (2003). She shows the underbelly of femininity with subtle, captivating visuals that you never forget the films years after watching them.

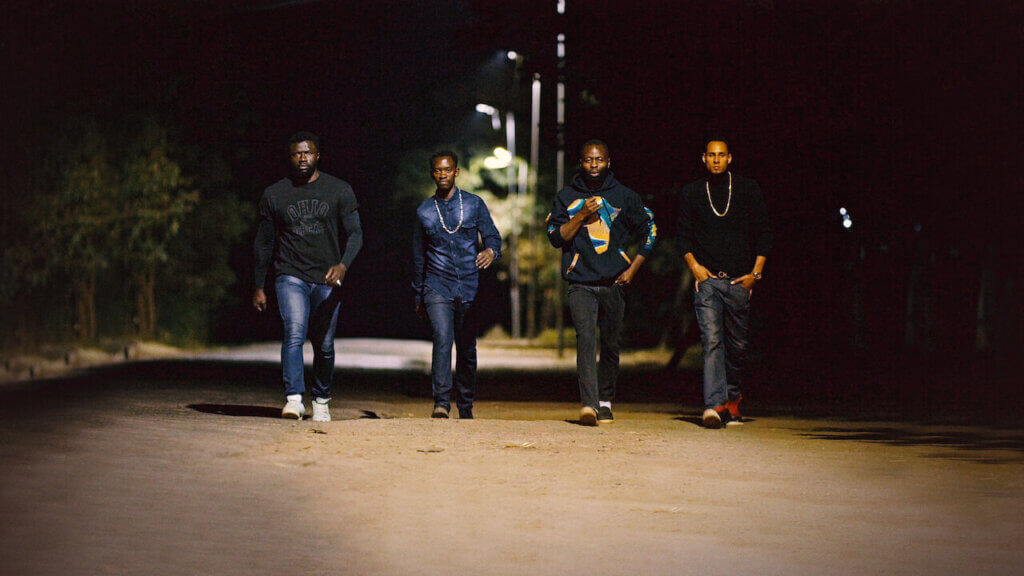

I’m not saying that our films aren’t entertaining, many of them are. I would shoot anyone who says Victor Gitonye’s 2020 film 40 Sticks wasn’t entertaining. But was it art? The screenplay written by Voline Ogutu works hard enough on characterisation, but clearly has no idea how the Nairobi’s riffraff talk today. 40 Sticks’ characters talk like they’re straight off a Shujaaz comic from 2008. For the most part, the dialogue is wooden, uninteresting, and burdened with mind-numbing exposition. Where is the flair of great dialogue? The subtext, the oomph, the heartbeat. Robert Agengo is expectedly brilliant in his role but the plot’s generic and limited scope further dulls any attempt by Gitonye to make anything worthwhile with his talents. And while cinematographer Enos Olik’s innovative use of tight shots in the darkness makes for an entertaining viewing experience, it does little to elevate the film to any memorable level.

And no, we don’t have to invent a completely new genre, or anything so drastic. The point is, what else can we do with our beloved crime drama to make it fresh, captivating, and reflective of contemporary Kenyan pop culture? In 1999, the US experienced an acute paradigm shift in cinema with the release of some of the most bizarre, innovative, thematically provocative, and most importantly, memorable and culturally relevant films. Think of The Talented Mr. Ripley, The Matrix, Fight Club, The American Beauty, The Virgin Suicides, Being John Malkovich, Magnolia, and Girl Interrupted. These films were (and still are) so impactful that 1999 has been famously dubbed ‘the golden year of film’.

But why were these films so iconic? 1999 was a peculiar year for the American culture. The Western society was increasingly getting digitized, and for the first time, computers were taking charge of critical assets that ran everyday life – from transportation to finance to health to governance. There were even predictions of a global shutdown and consequential Armageddon, rumors that elicited fear across the largely Baby Boomer and Gen X population. Middle-aged Boomers had become the new middle class, bored in their fancy office managerial jobs, while the Gen X – who had grown up amid the economic fears of the oil crisis and had seen technology become a radicalizing force with the rise of the dot com – led a listless, nihilistic lifestyle. The two generations shared resentment, with Boomers seeing Gen X as useless and aimless, while Gen X viewed Boomers as sellouts, traitors to the tenets of hippiedom.

The films of 1999 tapped into these cultural anxieties, extensively exploring these nihilistic feelings, essentially telling the audience, “Feeling hopeless and lost? Well, you’re not alone”. Many protagonists in these films were trapped in drab office jobs or monotonous, meaningless middle-class life. What made these films truly great was how they were able to crack at the American identity, particularly the tenuous facade of the American Dream. An Esquire article praised the films – Fight Club, American Beauty and Office Space – for depicting “the American male eschewing societal norms and sometimes literally fisticuffing against consumerism, suburbia, and complacency.” American Beauty was also praised for tapping into “a feeling that had been building throughout 1999 — that something about the country (America) was slightly off.” These films also tapped into the Boomer, Gen X wars and were not afraid to comment on the then US President Bill Clinton’s sex scandal.

Closer to home, Ousmane Sembène, widely regarded as the father of African cinema, is especially renowned for using film as a sense of identity. Starting out as a novelist with highly acclaimed works such as O Pays, mon beau peuple! (Oh country, my beautiful people!, 1957), Sembène soon realised that his literary work only reached cultural elites, whereas through films he could reach a much broader African population. In 1966, he released his first feature, La Noire de…, quickly cementing his distinctive cinematic style rooted in telling African stories through an authentically African lens. Sembène’s films were deeply political and socially conscious, artfully tackling decolonization and cultural identity. In Mandabi (1968), he reflects on the realities of everyday life in post-colonial Africa, drawing from real-life events and focusing on the struggles of ordinary people, particularly the marginalised and the poor.

Sembène masterfully balanced entertainment and art. In Black Girl (1966), he used a minimalist visual style, simple sets, and rich visual metaphors to convey complex themes of alienation and African identity in foreign Europe. His politically charged and aesthetically innovative films—particularly Emitai (1971), Xala (1975), and Ceddo (1975)—offer invaluable lessons. Film essayist Yasmina Price noted that in these films, Sembène was able to “break apart and remake the cinematic codes of time and spatial cohesion.”

Our history remains largely unexplored in Kenyan cinema. We’ve excelled in historical fiction novels, from Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o’s pre-colonial works to Marjorie Oludhe Macgoye, Grace Ogot, and Meja Mwangi. But in cinema? Almost nothing. Through Emitai, Xala, and Ceddo, Sembène “critically evaluates the unfolding of Senegalese history” from anticolonial resistance as in Emitaï to the hypocrisy and corruption of post-colonial Senegalese government as in Xala where Yasmina writes that Sembene exposed how the elected government officials “failed their own people by flaccidly depending on colonial power to maintain a mirage of authority.”

Kenyan cinema needs a revolution, right now. Our approach to genre must evolve to incorporate our history, culture, and the realistic sensibilities like Gen Z and millennials’ apathy to formality, predictability, and traditions. Would an educated but unemployed Kenyan youth resort to petty crime as they might have 20 years ago, or would they opt for the more sophisticated wash wash schemes? Where are the cool, cerebral heist films featuring characters with law degrees from UoN and computer science degrees from JKUAT? Perhaps we should explore the film noir subgenre—crime dramas that probe moral ambiguity, reflecting a society where our president publicly professes Christianity while still being, well, him.

Imagine if our crime dramas could focus less on glorifying poverty-born crime and more on moral ambiguity and urban isolation, themes that are particularly relevant to Kenyan society today. Think of the works of director Michael Mann, especially his 1981 film Thief with the moody electronic score and curated, highly stylized visuals. Noir is a crime subgenre with a huge potential that remains unexplored. Think of Kenyan versions of neo noirs like the cynical western, No Country for Old Men, or Tarantino’s oeuvre of graphic violence.

Our writing is dumbed down to an absurd degree. A senior local producer once told me that Kenyan audiences aren’t smart enough for intricate plotlines. This, about the same audience that flocks to Game of Thrones trivia nights and keeps Prison Break and Breaking Bad relevant years after they aired. Shows like Money Heist and Squid Game topped Kenya’s Netflix for weeks. Our dialogue is so trite, basic, and unimportant that you can watch most Kenyan films on mute. Forget the cinematography feats and otherworld visual effects; dialogue is one of the most important elements of great storytelling. No amount of money or talent can make bad dialogue work. The dialogue in a film like Sincerely Daisy would still be bad even if you had Zendaya playing the eponymous leading role. Great dialogue should have rhythm, subtext, and heart—think Little Women (2019), Queen & Slim (2019), Get Out (2017), or the masterful conversations in Tarantino’s films.

Most of the time, our characters are uncompelling archetypes with no depth. Where are our multilayered, world-weary protagonists and femme fatales? You know, characters that are fully fleshed humans, not the ‘Bad Guy who’s evil’ and ‘Good Guy who’s always positive’ trope. Well written characters elevate a story beyond what even the Meryl Streeps and Denzel Washingtons of the world can. Our characters must have agency, some edge. Supa Modo’s Stycie Waweru might even have been an Oscars contender if her character was better written.

Kenyan cinema must reinvent itself. We must evolve. We must invest in directors with personality and well-defined artistic pursuits. We must push into the future with daring creative visions, and stories rooted in our cultural insights. Let’s make Kenyan cinema great again and again.

Well thought out and written article! I agree with it 100%.