The rest of the country remembers him as a doe-eyed independence poster boy, a man of charming wit and brilliance who helped birth Kenya’s first constitution and lay the foundation for its economy. But in South Nyanza, my father’s generation and those before him would rather forget this man. Tom Mboya is a memory that leaves a bitter taste for those old enough to remember him as a man, not the legend he is today. That’s what he was to my kinsmen, or so my father once told me, a man. A brilliant man whose powerful intellect outwitted the white man and got him killed for it—but still just a man. A boy. The son of Leonardus Ndiege JaRusinga. Among the older generation in South Nyanza, his name evokes head-shaking and spitting as they say, “Jarateng okohero ng’ama riek” (A Black man does not like a clever person).

When I took my seat on Saturday, 23 November at Jain Bhavan auditorium, packed to capacity with Kenyans about to witness a play about Tom Mboya’s life and legacy, I thought maybe my kinsmen were wrong. Maybe Black people do like clever people.

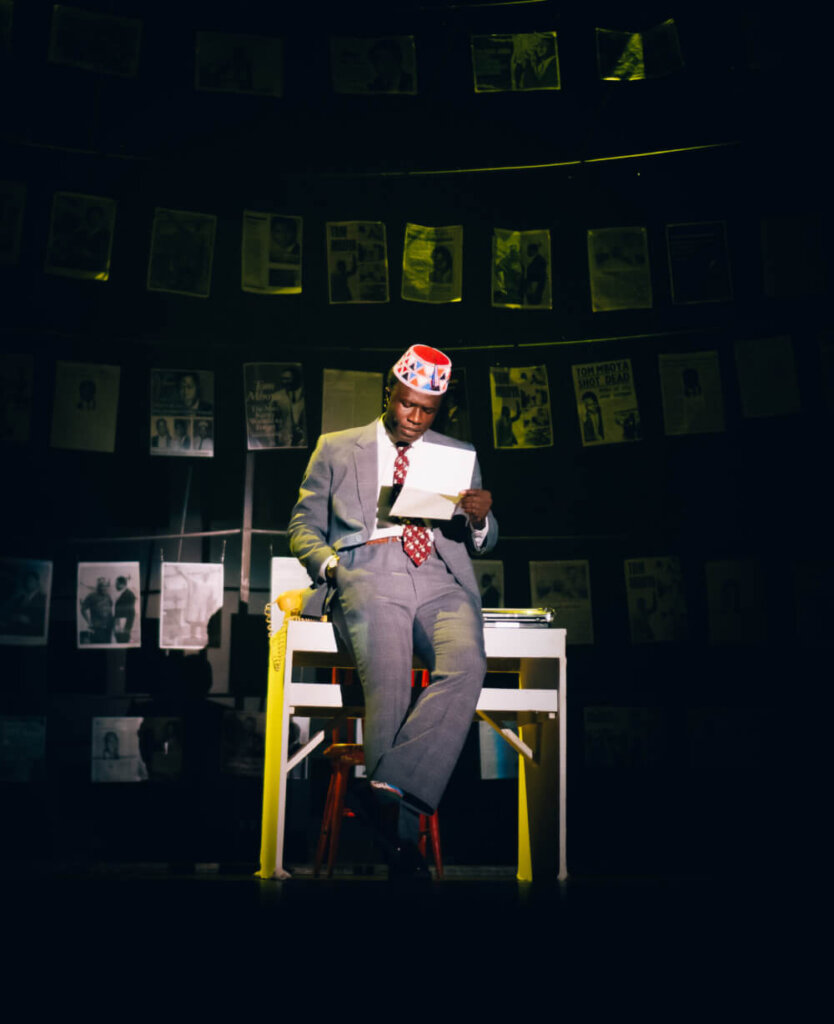

Titled Tom Mboya, the play is the work of the ambitious Kenyan theatre group Too Early for Birds, showcasing the collaborative genius of a team dedicated to reviving Kenya’s rich history. Directed by Mugambi Nthiga, from a script by Bryan Ngartia, Wanjiku Mwawuganga, Hellen Masido, Mercy Mutisya, and Magunga Williams, the story unfolds through a talented ensemble cast. Ywaya Xavier delivers a commanding and suave performance as Tom Mboya, supported by standout contributions from Elsaphan Njora, Nyokabi Macharia, Doanna Owano, Anubhav Garg, Martin Kigondu among others. Together, they craft a layered and poignant narrative that balances history, humor, and tragedy with remarkable finesse.

From the start, Tom Mboya felt like slipping into a fever dream. The story, whose tragic end we already know, unfolded like a haunting descent into quicksand—every glimmer of solid ground only revealing itself as a trap. At times, it felt suffocating, and yet, amidst the heaviness, the play constantly broke the fourth wall to inject the much-needed humor. The audience erupted in the kind of laughter the Hindu gods in the temple below probably disapproved of at witty jabs like “Why was Kenyatta stoned?”

We laughed at ourselves – a nation unable to escape its own murk. We laughed at our gaucherie, our problems, and at the politics that have smudged this nation for six decades. We laughed to restrain ourselves from storming the streets June 25 style, right there and then. We laughed about the brilliant pop culture nods from Uncle Ruckus references to Jomo Kenyatta being christened ‘Kapenguria Six lead singer.’ But when we were not laughing, Tom Mboya egged us out of our lethargic complacency, masterfully balancing moments of levity with deep introspection, forcing us to confront how far—or how little—we’ve come as a nation.

Mbuya KaNdiege—as he’s fondly known in South Nyanza—was a remarkable man, the kind who comes along once in a generation. By the age of 38, he had already shaped Kenya’s independence, spearheaded the Airlift Africa program (which launched talents like Barack Obama Sr.), and drafted the famous Sessional Paper No. 10: African Socialism and its Application to Planning in Kenya —a blueprint for the country’s economic future. Mboya was an intellectual giant, a political force, and a symbol of hope.

From a simple set, much unlike the sartorial elegance of the man the show is resurrecting, the politically charged play tells us that as a country, we’ve been trapped in our own body for 60 years. Governments come and go, but the systems of oppressions and violence – assassinations, extrajudicial killings, police brutality – persist. Not to mention the rampant corruption, and political betrayals that are as true today as they were in Mboya’s time. But there’s hope, this play tells us. “We have a right to be free. We’ve always had a right,” a defiant Ywaya Xavier (playing Mboya) says in the closing monologue. Through its almost four-hour run, the play jolts us out of complacency. “Pay attention. This is important,” it urges.

The genius of Tom Mboya is not just in its extensive research, pulsating writing, riveting performances, or creatively minimalist stage design. Its brilliance lies in crafting an immersive experience that, as I once wrote for The Republic (forgive the indulgence), “transcends the physical and auditory manifestations.”

We’re not merely watching these actors reenact Mboya’s life—we’re right there with him in the 1950s, rising through trade unions, and later in the U.S., brushing shoulders with icons like Martin Luther King Jr. and John F. Kennedy. We experience what being Tom Mboya must have felt for Tom Mboya. The dashing young man with a round face, full of the Nyathi spirit of his Luo heritage, and dreams far larger than his tragically short life.

We see his layered existence: the fierce intellect that wrested Kenya from colonial rule, but was also employed for his selfish political machinations. His quiet charm, used to secure transformative deals like the Kennedy Airlift program, and also to charm “women like sukari nguru” (to quote the late veteran journalist Philip Ochieng).

The closing scenes are heart-wrenching. Dressed in black, the cast mourns as they sing Eric Wainaina’s Daima, while archival footage of Mboya’s requiem mass flickers onscreen. Tear gas and scenes of police brutality erupt with a chilling familiarity, a stark reminder of how little has changed. We mourn a man who has been gone for 55 years with such palpable grief. Just a few seats behind me sits Mohini Kaur Sehmi, the now 90-year-old pharmacist who tried to save Mboya’s life after he was shot. Onstage, her character is brought to life by Chadni Vaya. I watch as she quietly dries a tear, a poignant reminder that she still lives in a country governed by forces not so different from those that silenced him.

We mourn our nation and the lives lost in our long struggle for true freedom. From Pio Gama Pinto, JM Kariuki, Robert Ouko, to Rex Kanyike Masai and all those fallen since the June 25 protests. My eyes well up as the cast, with the Kenyan flag raised high, chants their names. The scene shifts, showing solidarity with oppressed peoples around the world: Palestine, Congo, Sudan, Mozambique.

This is a moment of defiance: We cannot be stopped! We will not be silenced! The fight for progress continues until we live in a country of moral laws, a nation that wages war on poverty—not its people.

For its final introspection, Tom Mboya tells us the play tells us the ‘who’ and ‘what ifs’ of his assassination no longer matter. What matters is whether we – the youth – have what it takes to keep challenging the status quo like he did. Will we demand freedom from corruption, ethnic divisions, police brutality, gender-based violence, and deceit? Will we fight for true freedom?

As the curtains fall, we rush out—running from something, or perhaps toward something. From grief to resolve, we hurry out with the revolutionary fire burning in our hearts. I think Tom Mboya would have liked that.

Too Early for Birds will return for a final staging of Tom Mboya. Dates to be confirmed soon.