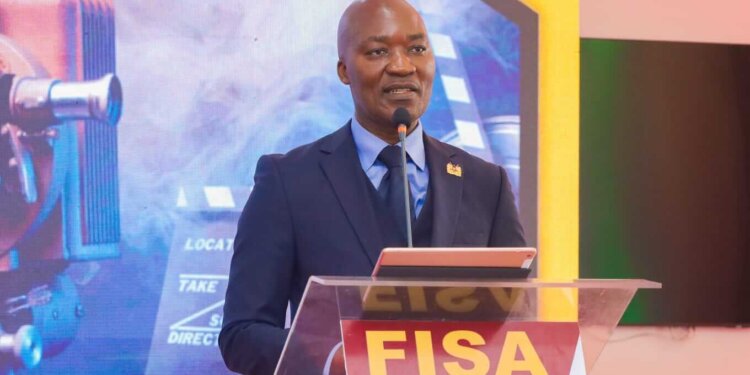

The Kenya Film Commission (KFC) released its long-awaited Film Industry Satellite Account (FISA) report on 28 November, finally putting figures behind many mysteries that have left most of us in befuddlement and confusion for years. We finally have some numbers to work with. Before we delve into what’s what, it’s important when reviewing this data to remember that 2020, on any analytical chart, serves as some kind of obstruction that alters the natural progression of things due to the COVID-19 phenomenon, nonetheless, we now have a working theory about what our industry looks like, and perhaps even enough data to speculate what it could look like in future.

The biggest impression I received upon going through the forty-nine-page report, prepared in collaboration with Kenya National Bureau of Statistics and GIZ Kenya, was growth and upward mobility, not just for the film industry but for the country in general. It’s a symbiotic relationship, and it’s almost impossible for a country to advance while leaving behind its film sector, especially when those advances are technological. In the first pages, the report explains how this information was compiled and the methods used to pool this data. It was mostly done to imitate film industry satellite reports from other countries, like Japan, Thailand, and South Africa.

This report is welcome, but I find it a little underwhelming in its thoroughness. Some novel information includes the number of film distributors operating out of Kenya yearly, dwindling from over 6,000 in 2018 to just over 3,000 in 2022. The report mentions that in Kenya, film distribution has been ‘informal for many years due to the lack of cinema theatres in most parts, leading to informal distribution methods like self-distribution or piracy. Film distribution is mainly undertaken by movie libraries and movie shops that are spread across the country.’ It’s still completely unclear who they considered legitimate distributors and who they wrote off, but with the figures posted here, it seems they might’ve even included local accounts that torrent on sites like thepiratebay. Any person can look at our film landscape and tell you we don’t have one hundred real film distributors, as the report claims.

Cinema screens, as we’ve mentioned here, are disappointingly low in count. Kenya has a total of 14 cinemas, with 32 screens in Nairobi (11 theatres), three in Mombasa (one theatre), and two in Uasin Gishu and Kisumu (one theatre each). We’ll get back to these numbers in a little bit. The report describes the role of licensed film exhibitors as ‘undertaken through cinema halls commonly known as video shows that have created a platform for foreign content to be accessed by the Kenyan audience.’ The numbers here are alarming, to say the least – a drop from 33,710 in 2018 to 3,872 in 2022. Even more alarming is their lack of proper definition and distinction between a film exhibitor and a film distributor, evidenced in the report using the two terms interchangeably. Allow me to clarify, and maybe next time, we’ll get more accurate data. A film distributor is a party responsible for getting the film from the hands of the producers and filmmakers, once ready, and into the hands of the film exhibitors, which one would think of as cinemas or streamers and whatnot. Let’s just hope it was a typo.

Also Read: Cinema Culture in Kenya and Why We Must Win the Goodwill of the Audience

Film festivals also get a mention, playing a ‘big role in the validation of the art of filmmaking.’ The numbers are on an up and up, reporting about 17 in 2022. The upcoming Kalashas Awards, postponed to March 2024, are being hyped as more than just an award but an entire festival – a long-overdue advancement in Kenya’s film ecosystem.

FISA also reports that copyright registrations have seen a drastic downturn from 11,885 in 2021 to 2,503 in 2022. This might mean fewer people are creating works, and we can certainly see it in our annual output of films this year being lower than in 2022. Otherwise, perhaps creatives are leaning more towards not registering their projects. This takes us to ancillary territory, such as the supporting industries.

A film industry has so many spires it touches everybody in some way, every industry, in fact. All things considered, the employment divide in the Kenyan film industry is categorised like so: the wholesale and retail trade take up about 37%, the professional and technical activities (the actual film stuff) take 30.9%, service activities 13.5%, and other economic activities 18.6%. When comparing broadcast to film, film edged television out by a few inches in every regard, for instance, employing more people in 2022 with 29,635 jobs as opposed to broadcasting’s 14,427 jobs. We have a 0.4% share in the international film market. Most definitely rookie numbers. We need to get those up. Way up.

This report also contains several graphs of data detailing our broadband growth, the amount and type of television sets found in Kenyan households, internet speeds, and other topics of free domain since the 2019 general census. Remember, I called the report a welcomed resource but thoroughly underwhelming for its lack of… thoroughness. It feels phoned-in. Thailand (or wherever) is not in the same historical, geographic, economic or narrative place as Kenya’s film industry. Sometimes, I think the industry decision-makers in suits don’t understand just how nuanced our position in this market is and how different it is from almost any other in the world. For instance, when I received the report, I was very excited to finally get my hands on official box office numbers, only to discover that all the information had been coalesced (or guessed – rounded off) into the nearest most colourfully graded graph they could make. Before getting into the actual data, the report itself apologised for this, stating, ‘film-industry specific data, such as production budget, box office revenues, and employment figures were not always readily available or accurately recorded.’ Which begs the question: why does this report exist… exactly?

You could say to estimate this industry’s contribution to the nation’s overall GDP. That’s very important, so I say it’s very welcome. But what’s even more important now is film industry data that will work for the film industry, not as a part of a GDP overview that’s so negligible it isn’t even necessary to inspect. We need more accurate data, like box office data. The step they skipped over to produce this surface-level report is, in fact, the job KFC needs to do. They need to, or for God’s sake, someone needs to make sure that, somehow, that ‘film-industry specific data’ finds its way to the people who are interested and invested in the film industry in this country. 32 theatres in Nairobi and they didn’t even bother to find out which ones aren’t multiplexes controlled by Hollywood studios, which ones were ours; how many theatres and screens do we really have? That’s the kind of information I’m really interested in, especially as we look towards making film and cinema a culture, a business and a sustainable contributor to the country’s GDP.

When we asked for a ‘film industry satellite account’, I admit, perhaps we didn’t even know what it was exactly. But now that we have it, can we ask for more comprehensive data?

Read the full report here.

Enjoyed this article?

To receive the latest updates from Sinema Focus directly to your inbox, subscribe now.