Emmanuel Esomnofu, One of the most versatile culture commentators in the continent, describes Mami Wata, the first homegrown Nigerian feature film to premiere at Sundance Film Festival, as a film that “makes a strong argument that it belongs among the canon of modern Nigerian cinema.” This praise largely mirrors the acclaim that the CJ ‘Fiery’ Obasi-directed film has received from critics in the continent and beyond since its global festival run, and eventually, cinematic debut in Nigeria in September. Therefore, it was hardly a surprise when the Nigerian Official Selection Committee (NOSC) announced Mami Wata as Nigeria’s contender for Best International Feature Film at the 96th Academy Awards.

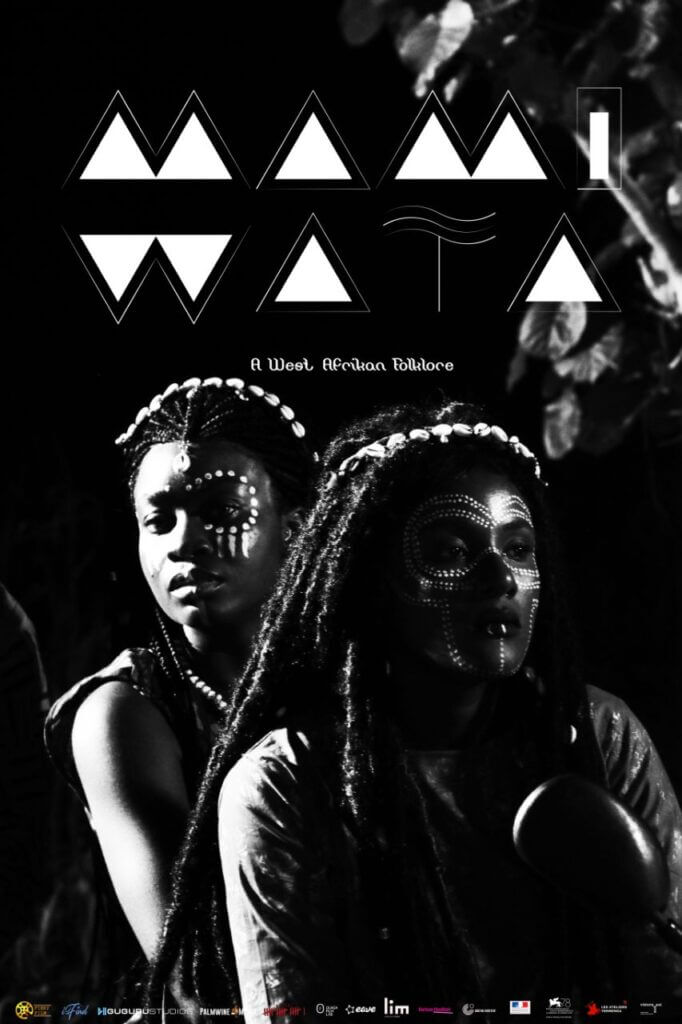

Mami Wata is the narration of a character who, in Swahili folklore, is termed as Mamba Mutu. Told using exquisite monochromatic black and white visuals, Mami Wata is the story of a community known as Iyi, the dwellers of an oceanside village (a quick Google search reveals the setting to be in rural Benin, a place so similar to rural coastal Kenya in both outlook, cultural beliefs and practices) where the matriarch, Mama Efe (Rita Edochie), confronts a challenge similar to the one any leader in an orthodox society encounters: the people start to question if their indigenous ways are pertinent to any benefits as the enticement to embrace modernity increases.

Mama Efe has two daughters, Zinwe and Prisca (portrayed by Uzoamaka Aniunoh and Evelyne Juhen respectively), whose performances are arguably the most commendable in the film. The beliefs of the two differ a bit as Prisca, who is adopted, sees logic in the concerns of her fellow villagers about the relevance of their current way of life, while Zinwe still seems to have some belief in her mother’s ways, although she seeks assurance. The pivotal happening in the film is the washing up at sea of Jasper (Emeka Amakaeze), whose arrival becomes the harbinger of a slight shift in the motif of the film because of how his subsequent actions prove to be satirised narrations on political conflicts, which are put in juxtaposition with the already established theme of African otherworldliness from the start of the film.

Obasi’s ability to make this African-centric fable narration a microscopic study of subcultural relations and conflicts as well, reveals the markings of a truly talented filmmaker. His employment of a hyper-sensitised aesthetic to the film, which in an interview with CNN he had described as the cinematographer’s (Lìlis Soares) attempt to understand how to capture dark and African bodies, shows Obasi as a creative who aims to not only explore his Nigerian identity but also his essence as a black person in a prejudiced world.

In a call to discuss the film with fellow culture critic and Nigerian Chimezie Chika, whose review on Mami Wata argues that the film is an exploration of the politics of power, he shares with me some of the reasons why critics and film enthusiasts have high hopes for Mami Wata at the Oscars. “We all know there is a set of criteria by which a film is judged. A film succeeds when it combines excellent cinematography, tight plot, good storytelling, and exceptional acting. A good film can meet all these criteria to varying degrees of success. But great films take one or all of these a notch higher. The director might take risks by being creative in how the individual scenes are interpreted through the cinematography and acting.”

“For instance, look at a film like Francis Ford Coppola’s The Godfather which achieves near-perfect excellence in everything that makes a great film. Sometimes, some elements may fall short in a film, but the transcendent acting elevates the film to a level of excellence. You see this a lot in adaptation films with great emotive actors like Meryl Streep. In some instances, innovative cinematography elevates the film; how the camera is manipulated to show mood and ambience. Magic is achieved when a director has that creative knack for detail, like say, Stanley Kubrick. When you watch any of his movies, you get to witness what the combination of camera and score can do. Mami Wata combines highly artistic, innovative cinematography and great acting. The scenes and set design are so visually satisfying they look like the finished canvas of a great painter. These are the combinations that make it an excellent film. And although I thought the plot was a bit rushed, other elements thereof elevated it.”

Chika also argues that another reason is the film’s subject, the deity Mami Wata, whom monotheistic western religions demonise but most in West Africa venerate and respect. The film celebrates the deity and accords her a deserved place in contemporary culture and art. Mami Wata is a spiritual film that projects the innate cultural identity of Africa. A film that uses ‘Blackness’ as a metaphor for manifold connections and significations.

In the aftermath of Mami Wata’s Oscar selection, director Obasi penned an emotional letter describing the achievement as “a call to arms and support for all who dream and aspire for a new narrative around us, and around our stories.”

As artistic and as great of a film as it is, one important question lingers: will the Academy give Mami Wata a real fighting chance? History would dictate that we should all be sceptical simply because African films haven’t fared well at the Oscars since the Best International Feature category (formerly known as Best Foreign Language Film) was introduced in 1956. To date, only 10 African films from 5 countries have been nominated in this category, and only three have won: Z (Algeria, 1969), Black and White in Colour (1976, Ivory Coast), and Tsotsi (2005, South Africa).

While European countries continue to dominate this category, Africa continues to be underrepresented despite an increase in entries even from first-time participants each year, triggering debates about Africa’s place in the eyes of the Academy and whether they even take African cinema seriously in the first place. According to Tambay Obenson, founder of Akoroko, in his piece Weighing the Pros and Cons of African Films in the Oscars Spotlight, the continent’s underrepresentation could be attributed to “the global audience and jury lacking the contextual understanding to fully appreciate the nuances of African narratives, which could lead to misinterpretations or oversimplifications of the films.”

On a larger scale, this cultural bias towards Africa speaks to the Academy’s diversity problem which has drawn criticism for years and, most notably, prompted the #OscarsSoWhite movement created by activist and writer April Reign to challenge the fact that white players in the industry seemed to receive most, if not all, of the nominations and wins at the Oscars as opposed to their counterparts of colour.

2023 has been a heavyweight year for African cinema, with the continent submitting undeniably its strongest films yet, pictures with significant international recognition and critical acclaim. From Sudan’s Goodbye Julia which looks at class differences amid political turmoil, to Senegal’s Banel And Adama which is a narration of two lovers in conflict with their social environment and responsibilities, to Burkina Faso’s Sira where a young woman takes a stand against Islamist terror after a brutal attack, to Morocco’s The Mother of All Lies where a woman’s search for truth tangles with a web of lies in her family history, just to name a few. And our very own Kenyan submission Mvera, a story inspired by early freedom fighter Mekatilili Wa Menza, has been described by film critic Churchill Osimbo as “the best Kenyan film yet” while also praising the film’s lead Linah Sande as having delivered “the best lead performance in Kenyan history.”

While it would be significant to see more African films on the Academy’s Best International Feature 2024 nomination list, for this critic and many others, Nigeria’s Mami Wata could be our best chance at receiving both a nomination and a win.

Rated four stars on RogerEbert.com, the highest rating a film can attain at one of the leading film criticism platforms in the world, what makes Mami Wata a strong contender is not only its artistic exploration of a fable deeply rooted in African mythology but also its success as a film that has received high praise and acclaim internationally which might be optimal for the Academy. But the competition is stiff, and Mami Wata would be going against highly rated European films such as France’s The Taste of Things which critics have termed to represent the country’s best chance of winning the category since 1992, and Germany’s The Teachers’ Lounge which is a prolific exploration of personal ideologies. However, it is high time the Academy disproved those claims of biases against Africa by recognising the dexterity of filmmakers in a continent they have significantly failed to honour before. And what better picture to deliver a long-overdue fourth win for the continent than Mami Wata.