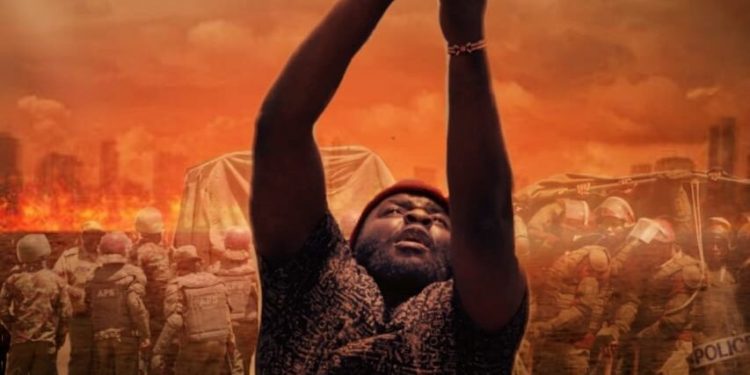

By definition, Bangarang is a Jamaican slang to mean disturbance or disorder and no more fitting title could suit this 88 minute feature film that greatly centres the 2007 post-election violence and the repercussions that follow. It joins the ranks of notable films that share the same central theme, the likes of, Something Necessary (2013) and Ni Sisi (2013).

Bangarang is technically the first Kenyan film to stream on Amazon Prime Video (if you don’t count the Amazon Prime rentals for the likes of Rafiki and Softie). The film is written and directed by Odongo Robbie who has previously directed, as well as produced three award-winning feature films in his vernacular Luo language – Seredo 1, Seredo 2 and Jonarobi. The plot of the film follows the protagonist Otile (David Weda), a 30-year old second-class honours graduate in automotive engineering (this information is repeated throughout the film) who has been searching for a job for a long time. However, with the onset of the election violence after the disputed Kenyan presidential elections, and the brutal killing of his father at their home by an unknown assailant, Otile decides to lead other rioters to protest in the streets of Kisumu.

He rightly argues out, that his actions are a means of venting out his anger and frustration to a government of poor leadership, which has constantly failed his people in the Luo community who in the society, are politically overlooked and are riddled with negative stereotypes each election year. Otile explains to his girlfriend Njeri (Wendy Mokua) who comes from the Kikuyu ‘privileged’ tribe, how having a Luo name makes it hard to get a job, . One would think that tribalism would shrewdly play out as a key factor within the film. Instead, we see a very shallow portrayal and lame version of tribalism between these two tribes (Kikuyu and Luo), with each throwing underhanded comments at each other. Sadly, this makes the entire sensitive issue of tribalism come across as an after-thought.

With a goal in mind – for the government and the rest of the nation to hear his grievances and those of his people, Otile heads out each day to protest in the streets, and to demand that their leader Jakom, be put in power. Armed with only, a rock and a rope, to sling at the bullet proof, heavily-armed police officers, he confidently charges forward. One fateful day, while being pursued by anti-riot police officers patrolling the area, Otile hides in the residence of Dan (Duncan Ochieng), a father a six-month-old baby, Joy, who is least interested on the political wars of the country. The police enters Dan’s home, and while carrying out their search, accidentally hits baby Joy on the head, fracturing her scalp and leading to her death. Her death is pinned on Otile and he becomes a wanted man, or so he thinks.

The film tone is well set from the beginning as the chaos that engulfs the region (Kisumu) translate on screen. The roads are filled with burning tires, crowds of angry protestors hurl stones at the police officers and heavy dark smoke fills the air. It’s a clear indication that the production investment of the Ksh 4 million budget from the Kenya Film Commission (KFC) and in-support kindness by the local government went a long way to bring a sense of authenticity. However, this is as far as Bangarang goes when it comes to believability. With lot of focus on great production design (done by Vigillance Atieno), the film disregards the script entirely.

To quote Charlie Chaplin: “Simplicity of approach is always best”, yet Bangarang fails to use this concept. For the viewer, it is quite clear that the main plot that the writer-director intended to go with, is police brutality, all culminating to re-telling the real death story of Baby Pendo (who Baby Joy symbolises). Officer Charles (William Ochieng) executes his role well as the soft-spoken integral officer in a system filled with corrupt and murderous police officers whose main mandate is to protect innocent lives and restore peace. To stick to this as the simple main plot, while still not losing the integral bit of post-election violence, would have made Bangarang way more impactful.

Instead, the constant overbearing and jamming down the entire film with many half-baked themes, with a touch and go style, gives it a very watered-down feel. For example, adding an unnecessary love story (which at some point, one wishes their relationship ended from the very first introduction), with the increasing annoying character Njeri, who is either love-struck or playing dumb. At no point do we invest in this Otile-Njeri love tale, as Otile makes it clear he is no longer interested in her but she somehow insists. This is one of the sub-plots, which Bangarang painfully suffers, as the ending draws from this relationship, in an anti-climactic finish.

As the protagonist, Otile comes across as a confused individual with no proper standing on what or where his principles stand. At one point, he vows vengeance on the government, holds a level of contempt against the Kikuyu ‘privileged’ tribe and easily dismisses anyone who does not support the cause to fight for Jakom’s rightful election win. However, by minute 29:35 he says, “Don’t pay evil with evil” in order to prevent people from lynching a cop. This random 360-degree turn from a character early into the film, without any significant turning point to make him change his mind, is beyond perplexing for a viewer.

Over-exposition dumps is another element in the script, one would think the writer feared that the audience would not understand anything. At all. Every story line had some unnecessary backstory and flashbacks to explain things as well as force an emotion from the viewers. Like it had to be known that Mama Joy suffered four miscarriages, so that we can have more sorrowful feeling to the loss of her child. Another case is that the only reason Officer Charles has veracity is because he always wanted to be a cop since he was a child and live by the oath to protect and serve – insert flashback of him as a young boy.

Film is a visual medium, and sadly, the poor lighting choices in Bangarang’s most scenes, especially night scenes, is gravely distracting to follow the story. The numerous drone shots that neither matches with the colour grade of the actual scene nor the actual maniac atmosphere created by the previous scene is unbearable. Having said this, the over-use of drone shots as a transition tool between scenes in most Kenyan films and series has now officially become hackneyed.

This not to say that Bangarang did not have its highs – the beautiful score by Ibrahim Sidede (You Again, Disconnect, Nairobby) did fill in the gaps to create the intended cinematic energy in every scene, and the locations (George Audi) painted the real picture of the situation on the ground.

As Bangarang nears the end, one hopes that the conclusion will at least salvage the really terrible script, which is not limited to the poor English speaking dialogue by actors, but alas! a twist awaits. Otile goes to Baby Joy’s funeral after fleeing to have his penance (which he chickens out of doing, no surprise there). Only then, does Officer Charles inform him that the government wants to hire him as their chief automotive engineer from the aforementioned degree, as a reward for saving a cop and that is why they put out the ‘wanted’ notice. He later reunites with his girlfriend Njeri and he proposes. With an uninspired and bathetic ending, one question stands out, did the writer really think any of this through? Probably, not.

Within the Kenyan filmmakers circles, the term ‘our stories’ will arise from time to time. This enigmatic word is one bound to stir many different responses, with a few claiming, no such stories exist instead only universal tales, while most agreeing that it means stories that stem from our own history as a people or even simply put, stories that we easily identify and relate to as Kenyans. So, why are we seeing less and less of such stories on our screens? Then again, the bigger question is, does filming our own stories equate to an instant success of a film? Bangarang won numerous awards with the two major ones being, Best African Feature Film at Durban International Film Festival 2022 and Best East African Film at 2022 Uganda Film Festival. You would be the better judge.

Bangarang is now streaming on Amazon Prime Video.

Enjoyed this article?

To receive the latest updates from Sinema Focus directly to your inbox, subscribe now.